Geographically weighted regression is a multivariate model that is taking into account non-stationarity across space. As the coefficients in GWR may vary across the inspected area, the method is an adequate tool to analyse local properties of the dependent variable.

Comparing with Ordinary least square regression, that generates a single equation for the global model:

(1) ![]()

GWR constructs a separate equation for every feature in the dataset incorporating the dependent and explanatory variables of features falling within the bandwidth of each target feature. The Geographically weighted regression equation is

(2) ![]()

where (ui, vi) represents the coordinates of the ith point in space. The cordinates for this model are the latitude and longitude coordinates of each polygons‘ centroid. The weight assigned is based on a distance decay function centered at location i and observations nearer to i are given greater weight than observations further away. The (global) ordinary least squares linear regression model assumes that the observations being

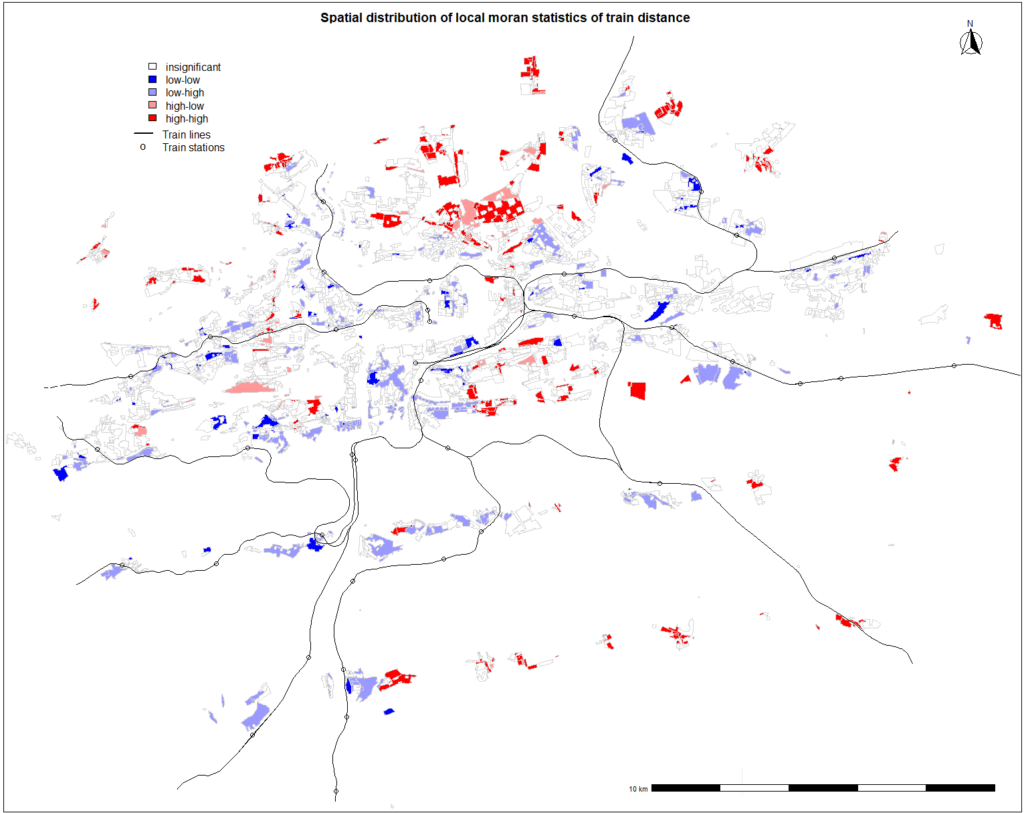

used are independent. As it was already explored in the previous chapter, this assumption is violated as there are significant spatial clustering patterns in the data. In Geographically Weighted Regression, this assumption is relaxed, as it allows for spatially varying coefficients by producing estimates

of the parameter at each data location, factoring in spatial heterogeneity.

Using OLS, the parameters for a linear regression model can be obtained by solving:

(3) ![]()

The parameter estimates for GWR may be solved using a weighting scheme:

(4) ![]()

The weights are chosen such that those observations near the point in space where the parameter estimates are desired to have more influence on the result than observations further away.

The Gaussian function is used for the weight calculation, the weight for the ith observation is:

(5) ![]()

where ![]() is the Euclidean distance between the location of observation i and location (u,v), and h is a bandwidth.

is the Euclidean distance between the location of observation i and location (u,v), and h is a bandwidth.